Browse: 1470 objects

- Reference URL

Actions

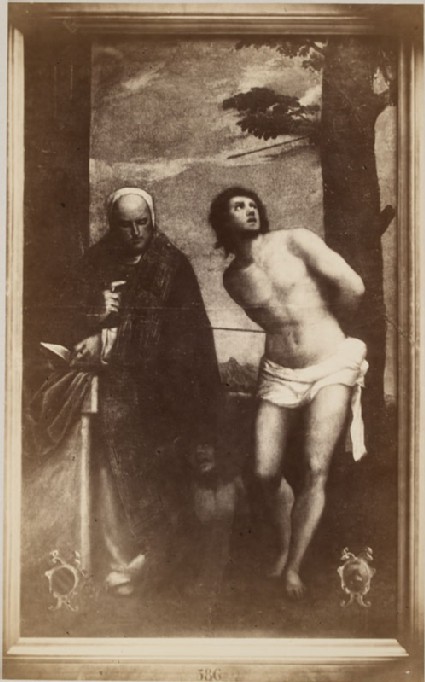

Photograph of Bonifacio Veronese's "Saint Sebastian and Saint Bernard" Anonymous Italian

-

Curator’s description:

Description

The painting depicts Saint Bernard on the left, wearing his heavy, white Carthusian habit beneath a dark cope, and with a grotesque figure, perhaps intended for the Devil or a personification of heresy, at his feet. Saint Sebastian stands on the right, his arms presumably tied to the tree-trunk behind him.

Ruskin only identified St Sebastian; Cook and Wedderburn identified St Bernard, and noted that the painting was in the Accademia, Venice. It was commissioned in 1531 or 1532 by Bernardo Contarini and Sebastiano Cappello for the Magistrato del Monte dei Sussidi in Venice.

The photograph is first listed in the Teaching Collection in the "Catalogue of Examples" of 1870, as no. 21 in the Standard Series - a position it retained in the 1872 catalogue of the series.

In his entry, Ruskin described the picture's specifically Venetian characteristics: its grand yet simple use of light and shade, which maintained the clarity and simplicity of the colours; and the clear framework, and particularly symmetry, of its composition. In his "Guide to the Academy at Venice", however, he chose instead to focus upon its condition, calling it 'sorrowfully repainted with loss of half its life. But a picture, still, deserving honour.'

-

Details

- Artist/maker

-

Anonymous Italian (Anonymous, Italian) (photographer)after a work attributed to Bonifazio de' Pitati (1487 - 1553)

- Object type

- photograph

- Material and technique

- albumen print

- Dimensions

- 341 x 212 mm (print); 456 x 373 mm (original mount)

- Inscription

- On the painting's frame, bottom centre, and so reproduced in the photograph: 586

On the back of the mount:

top left, in ink, in a copper-plate hand: S. Sebastiano

top right, same hand: Bonifacio

top centre, slightly lower, same hand: Orig.e Accademia Venezia

bottom right corner, in graphite: St 21

towards the bottom, centre, the Ruskin School's stamp

- Provenance

-

Presented by John Ruskin to the Ruskin Drawing School (University of Oxford), 1875; transferred from the Ruskin Drawing School to the Ashmolean Museum, c.1949.

- No. of items

- 1

- Accession no.

- WA.RS.STD.021

-

Subject terms allocated by curators:

Subjects

-

References in which this object is cited include:

References

Ruskin, John, Catalogue of Examples Arranged for Elementary Study in the University Galleries (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1870), cat. Standard no. 21

Ruskin, John, Catalogue of the Reference Series Including Temporarily the First Section of the Standard Series (London: Smith, Elder, [1872]), cat. Standard no. 21

Ruskin, John, ‘The Ruskin Art Collection at Oxford: Catalogues, Notes and Instructions’, Edward T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn, eds, The Works of John Ruskin: Library Edition, 39 (London: George Allen, 1903-1912), 21, cat. Standard no. 21

Ruskin, John, ‘Guide to the Principal Paintings in the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice: Arranged for English Travellers’, Edward T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn, eds, The Works of John Ruskin: Library Edition, 39 (London: George Allen, 1903-1912), 24

Location

-

- Western Art Print Room

Position in Ruskin’s Collection

Ruskin's Catalogues

-

Ruskin's Catalogue of Examples (1870)

21. St. Sebastian and a Monk. (Bonifazio.) Photograph from the picture in the Academy of Fine Arts, Venice.I oppose this directly to the Parnassus, that you may feel the peculiar character of the Venetian as contrasted with the Raphaelesque schools. Bonifazio is indeed only third-rate Venetian, but he is thoroughly and truly Venetian; and you will recognize in him at once the quiet and reserved strength, the full and fearless realization, the prosaic view of things by a seaman’s common sense, and the noble obedience to law, which are the specialities of Venetian work. The chiaroscuro of this picture is very grand, yet wholly simple; and brought about by the quiet resolution that flesh shall be flesh-colour, linen shall be white, trees green, and clouds grey. The subjection to law is so absolute and serene, that it is at first unfelt; but the picture is balanced as accurately as a ship must be. One figure dark against the sky on the left; the other light against the sky on the right; one with a vertical wall behind it, the other by a vertical trunk of tree; one divided by a horizontal line in the leaf of a book, the other by a horizontal line in folds of drapery; the light figure having its head dark on the sky; the dark figure, its head light on the sky; the face of the one as seen light within a ring of dark, the other as dark within a ring of light.

This symmetry is absolute in all fine Venetian work; it is always quartered as accurately as a knight’s shield.

-

Ruskin's Standard & Reference series (1872)

21. St. Sebastian and a Monk. (Bonifazio.) Photograph from the picture in the Academy of Fine Arts, Venice .I oppose this directly to the Parnassus, that you may feel the peculiar character of the Venetian as contrasted with the Raphaelesque schools. Bonifazio is indeed only third-rate Venetian, but he is thoroughly and truly Venetian; and you will recognize in him at once the quiet and reserved strength, the full and fearless realization, the prosaic view of things by a seaman’s common sense, and the noble obedience to law, which are the specialties of Venetian work. The chiaroscuro of this picture is very grand, yet wholly simple; and brought about by the quiet resolution that flesh shall be flesh-colour, linen shall be white, trees green, and clouds grey. The subjection to law is so absolute and serene, that it is at first unfelt; but the picture is balanced as accurately as a ship must be. One figure dark against the sky on the left; the other light against the sky on the right; one with a vertical wall behind it, the other with a vertical trunk of tree; one divided by a horizontal line in the leaf of a book, the other by a horizontal line in folds of drapery; the light figure having its head dark on the sky; the dark figure, its head light on the sky; the face of the one seen as light within a ring of dark, the other as dark within a ring of light.

The symmetry is absolute in all fine Venetian work; it is always quartered as accurately as a knight’s shield.