Browse: 1470 objects

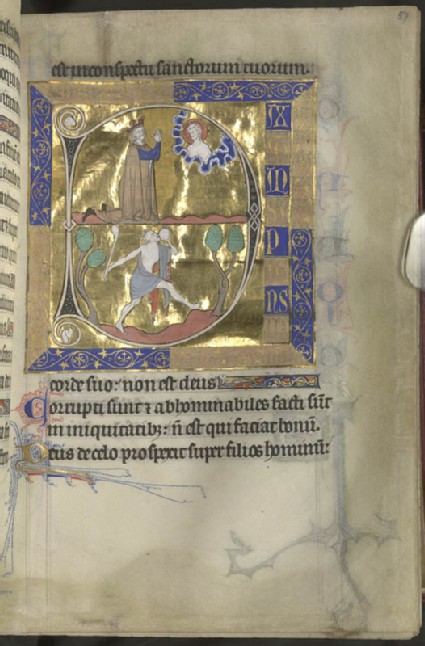

A Leaf from the Psalter and Hours of Isabelle of France, containing the End of Psalm 51 and Beginning of Psalm 52

-

Curator’s description:

Description

Described by Ruskin in the Standard and Reference Series catalogue as 'A Psalter, containing in its Calendar the death-days of the Father, Mother and Brother of St Lewis, - and without doubt, written for him by the monks of the Sainte Chapelle', the manuscript in fact contains a psalter and a book of hours. It was written and illuminated in Paris for Isabelle of France, sister of Saint Louis IX, King of France, at some point between 1252 and 1270.

The manuscript (together with the Hours of Yolande of Navarre, leaves from which were also in the Teaching Collection, amongst the unframed examples) was damaged whilst in the collection of John Boykett Jarman when his home in Grosvenor Street, Mayfair, was flooded on 1 August 1846 (not c.1854 as described by Ruskin). Backhouse notes that Jarman may well have employed William Charles Wing (active 1835-1860) to repair and, in some cases, retouch his damaged manuscripts.

Ruskin bought the manuscript from Jarman on 24 February 1854. He soon dismantled it, in order to circulate leaves amongst his friends and other collections: Dean Kitchin saw it in pieces in Ruskin's rooms at Oxford. Three leaves (folios 65, 117 and 118) were sent to Charles Eliot Norton, others eventually travelled to Brantwood. Notwithstanding, Ruskin listed the book as no. 1, 'Louis IX Psalter', valued at £1000, in the list of manuscripts stored in his Oxford rooms which he drew up for insurance purposes in his diary for 15 December 1872 (Ruskin Library, MS 18, p. 129). In a 'List of Missals' written in a volume of notes on Pindar and Horace, now at Yale (cited by Dearden), it appears again as no. 1, ‘St. Louis's Psalter'; the notes were written c.1879, although the list of manuscripts may be later.

In the catalogue of the Standard and Reference Series, Ruskin stated that 'I have placed the Manuscript itself, with a separately framed page of its calendar ... on the table in the larger room.' Three other leaves from the manuscript were framed as no. 6 in the Standard Series, and another three as no. 13 in the Rudimentary Series, where they were placed in the first section of the first cabinet, largely dedicated to heraldry. For an attempt to determine which leaves were placed where, see below.

After Ruskin's death, Joan Severn reassembled all the dispersed leaves (including Norton's) with the assistance of Sydney Cockerell, and sold the manuscript to Henry Yates Thompson in 1904, who had it rebound. The Fitzwilliam Museum acquired the manuscript in 1919. In order to persuade the Drawing School to part with its leaves, an exchange was arranged whereby the School would receive Ruskin's large study of Luini's "St Catherine" (on the wall of the Drawing School, now no. 1), some Dürers, and enlarged copies after the manuscript (also on the walls, now no. 15; for the exchange, see Panayotova, and Cook & Wedderburn, XXI.15 n. 2).

The identification of the particular leaves from this manuscript that were contained within the Teaching Collection is a complex matter, further clouded by the fact that Ruskin seems to have referred to the Psalms according to their numbering in the Authorised Version of the Bible, which differs from that in the Vulgate, which is the text used in the manuscript. For what follows, see the entries for Standard Series No. 6 and the accompanying note in the "Catalogue of the Reference Series"; the entries for Rudimentary Series No. 13 in the Rudimentary catalogues; Cook and Wedderburn, XXI.15 nn. 2 & 3; Hewison's edition of the Rudimentary catalogue, under no. 13; and Panayotova.

Three leaves were sent to Charles Eliot Norton and were never in the School; six were eventually placed in the School; one was in Brantwood, but was later placed in the School; and the remains of the manuscript were also placed in the School. Three of the School's leaves eventually found their way to the Bodleian, where they were bound into a volume of fragments from assorted manuscripts, Douce 381; there is a record in the Douce volume of the numbers of the leaves from Isabelle's Hours which it once contained.

Thus, seven leaves were in the School at one time or another; three are recorded as no. 6 in the Standard Series, three as no. 13 in the Rudimentary Series, and one on a table, where it accompanied the remains of the book (described in the entry for Standard Series no. 6).

According to a note in Ruskin's diary (Bodleian Library typescript, Eng. Misc C 236, fol. 65v) cited by Hewison, Norton was sent folios 65, 117 and 118. The following folios have been proposed for those held in the School:

xii: identifiable by 'the obituary sentence, written in gold, of the mother of St. Louis [i.e. Blanche of Castile], "Obitus Blanchiæ, reginæ Francorum," which it contains, described by Ruskin in the leaf on the table. It also carries annotations by Ruskin.

11: one of the leaves once in the collection and then in Douce 381, this contains 'the beginning ... of the 14th ... Psalm [Vulgate 13], with the latter verses of the 13th [Vulgate 12]', specified by Ruskin in his entry for No. 6 in the Standard Series.

23: proposed by Hewison, as it is referred to in "The Cestus of Aglaia" (XIX.100).

57: another of the leaves once in the collection and then in Douce 381, this contains 'the beginning ... of the 52nd ... Psalm [Vulgate 51] ..., with the latter verses of the ... 53rd [Vulgate 52]', specified by Ruskin in his entry for No. 6 in the Standard Series; it shows 'the D of "Dixit insipiens in (corde suo)"' described by Ruskin, with its 'large central letter'.

106: the final leaf once in the collection and then in Douce 381.

107: the subject of some confusion. In his catalogue entry for Standard Series no. 6, Ruskin refers to a leaf containing 'the beginning ... of ... the 99th Psalm [Vulgate 98]', which is on the verso of this folio, together with the end of Vulgate Psalm 97. However, this is not particularly spectacular; and Ruskin does not actually mention (as he does with the other two leaves from the Psalter in the Standard Series) that his Psalm 99 (Vulgate Psalm 98) shares the page with Psalm 98 (Vulgate Psalm 97). But, as the recto of the same folio, 107, begins with the beginning of Vulgate Psalm 97, Dr Panayotova suggests that this is the side of the folio which Ruskin displayed (personal communication, 17 April 2003).

177: proposed by Hewison, as it is referred to in "The Iris of the Earth" (XXVI.189), along with folio xii.

If folios 11, 57 and 107 were no. 6 in the Standard Series, and folio xii was on the table, this would leave folios 23, 106 and 177 to occupy no. 13 in the Rudimentary Series.

This folio, number 57, was therefore placed in Standard Series frame number 6.

-

Details

- Object type

- manuscript, drawing

- Material and technique

- bodycolour, gilding and pen and ink over lead point ruling, on parchment

- Dimensions

- 125 x 95 mm

- Provenance

-

Written for Isabelle of France?; Charles V, King of France; J.B. Jarman (c.1854); bought by John Ruskin, 24 February 1854; Joan Severn; sold to Henry Yates Thompson (MS no. LXXXV), March 1904; bought

- No. of items

- 1

- Accession no.

- CAMFZ.MS300.fol.57.r

-

Subject terms allocated by curators:

Subjects

-

References in which this object is cited include:

References

Backhouse, Janet, ‘A Victorian Connoisseur and His Manuscripts: The Tale of Mr. Jarman and Mr. Wing’, British Museum Quarterly, 32, (1967-1968)

Dearden, James S., ‘John Ruskin, the Collector: With a Catalogue of the Illuminated and Other Manuscripts Formerly in His Collection’, The Library, 5th ser., 21, (1966), no. 16

Ruskin, John, Catalogue of Examples Arranged for Elementary Study in the University Galleries (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1870), cat. Standard no. 6

Panayotova, Stella, ‘A Ruskinian Project with a Cockerellian Flavour’, (forthcoming)

Ruskin, John, Catalogue of the Reference Series Including Temporarily the First Section of the Standard Series (London: Smith, Elder, [1872]), cat. Standard no. 6

Ruskin, John, ‘The Ruskin Art Collection at Oxford: Catalogues, Notes and Instructions’, Edward T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn, eds, The Works of John Ruskin: Library Edition, 39 (London: George Allen, 1903-1912), 21, cat. Standard no. 6

Location

-

- The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Position in Ruskin’s Collection

Ruskin's Catalogues

-

Ruskin's Catalogue of Examples (1870)

6. Three pages of a Psalter, containing in its Calendar the death-days of the Father, Mother, and Brother of St. Louis,—and, without doubt, written for him by the monks of the Sainte Chapelle, while he was on his last crusade; therefore, before 1270.It is impossible, therefore, that you can see a more perfect specimen of the art che alluminare e chiamata in Parisi; and you are thus introduced to the schools of all painting, by the very work of which Dante first thought, when he spoke of their successive pride, and successive humiliation.

The three pages contain the beginnings of the 14th, 53rd, and 99th Psalms, with the latter verses of the 13th and 52nd. The large central letter is the D of Dixit insipiens in (corde suo) written. DIXIT INSIPIENS IN. The fool is represented as in haste, disordered and half naked, lost in a wood without knowing that he is so, eating as he goes, and with a club in his hand. The representation is constant in all early psalters.

-

Ruskin's revision to the Rudimentary series (1878)

Psalter of St. Louis 13.Entirely magnificent xiiithXIII Century work by French masters and in perfect state. Of course the genius varies in great schools as it does in little ones, and most sy M.S.S. show more genius in colour. None of the colour here is, properly speaking, fine, but it is entirely fine in the method and principle, that is to say, in the way it is laid on, and in the laws R. of interchange and gradation as far as they can be taught. No M.S. in the world of its date surpasses it in execution, and as M.S. it is a model of what is at once proper and beautiful. The text is the first thing thought of; the important clauses of this are indicated by beautiful letters, and the necessary pauses in this filled up by fanciful ornament. The grotesqueness and monstrosity of the animal forms are partly praiseworthy, and partly work of the devil, and it is altogether the devil’s work that one does not know how far the evil extends. One thing is certain, that such ornament can only be drawn out of redundant fancy, and if any students like to qualify themselves to imitate it, they must strictly follow its methods of colour and outline, while I wish them to introduce beautiful drawings of real animals instead of these monstrous forms. What else I have to say will be found in The Laws of Fiesole. These leaves are placed here as standards and no student should be allowed to waste time in unavailing efforts to copy them. Among the succeeding examples will be found progressive exercises for copying. [I said in describR. ing No.12 that the book from which the leaves are taken had escaped the destruction of the rest. The brown stain at the edge of the leaves shows to what point the water reached them.

-

Ruskin's Standard & Reference series (1872)

6. Three pages of a Psalter, containing in its Calendar the death-days of the Father, Mother, and Brother of St. Lewis, I have placed the Manuscript itself, with a separately framed page of its calendar, containing the obituary sentence, written in gold, of the mother of St. Louis, Obitus Blanchiæ, reginæ Francorum , on the table in the larger room. —and, without doubt, written for him by the monks of the Sainte Chapelle, while he was on his last crusade; therefore, before 1270.It is impossible, therefore, that you can see a more perfect specimen of the art che alluminare e chiamata in Parisi; and you are thus introduced to the schools of all painting, by the very work of which Dante first thought, when he spoke of their successive pride, and successive humiliation.

The three pages contain the beginnings of the 14th, 53rd, and 99th Psalms, with the latter verses of the 13th and 52nd . The large central letter is the D of Dixit insipiens in (corde suo) written. DIXIT INSIPIENS IN. The fool is represented as in haste, disordered and half naked, lost in a wood without knowing that he is so, eating as he goes, and with a club in his hand. The representation is constant in all early psalters.