Browse: 1470 objects

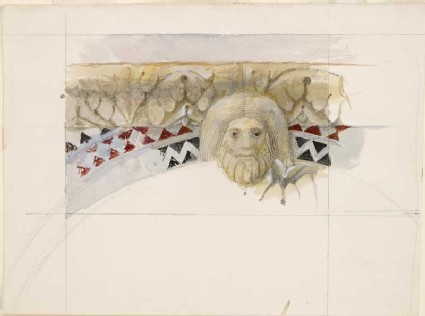

Study of a Head from a Panel on the Font of the Baptistery at Pisa John Ruskin

-

Curator’s description:

Description

According to Cook and Wedderburn (XXI. 34 n. 2), 'The Catalogue contained no Nos. 84-100, these examples having been added at various times after its issue.'

-

Details

- Artist/maker

-

John Ruskin (1819 - 1900)after Guido Bigarelli (active 1244 - d. before 1257) (sculptor)

- Object type

- drawing

- Material and technique

- watercolour and bodycolour over graphite on white paper

- Dimensions

- 257 x 350 mm

- Associated place

-

- Europe › Italy › Toscana (Tuscany) › Pisa › Pisa › Pisa Baptistery › Pisa Baptistery (subject)

- Inscription

- Verso:

towards top left, in graphite: Ref 99.

just right of centre, towards bottom, in graphite: T

bottom right, in graphite: Head from the Font | The Baptistery at Pisa

just below, in graphite (recent): Plate 37 Vol. 21 | Ruskin

right of centre, upside down, the Ruskin School's stamp

just above, in ink, upside down: M. 25

- Provenance

-

Presumably presented by John Ruskin to the Ruskin Drawing School (University of Oxford); first recorded in the Ruskin Drawing School in 1878; transferred from the Ruskin Drawing School to the Ashmolean Museum c.1949

- No. of items

- 1

- Accession no.

- WA.RS.REF.099

-

Subject terms allocated by curators:

Subjects

-

References in which this object is cited include:

References

Taylor, Gerald, ‘John Ruskin: A Catalogue of Drawings by John Ruskin in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford’, 7 fascicles, 1998, Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, no. 255

Ruskin, John, ‘Educational Series 1878’, 1878, Oxford, Oxford University Archives, cat. Educational no. 26

Ruskin, John, ‘The Ruskin Art Collection at Oxford: Catalogues, Notes and Instructions’, Edward T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn, eds, The Works of John Ruskin: Library Edition, 39 (London: George Allen, 1903-1912), 21, cat. Reference no. 99

Location

-

- Western Art Print Room

Ruskin's Catalogues

-

Educational, manuscript (1878)

26.In connection with the series of Greek Plants, given in the last cabinet, I am now going to give examples of Greek feeling for Colour and Form of the most elementary kind. But I place this for the first of the series because it at once explains, beyond any possibility of mistake, the essential points of Greek work, as distinguished from Barbaric. Primarily, Natural Life, as opposed to monstrous or inhuman; secondly, Order, as opposed to Phantasy and to Licence; and, lastly, the consummate grace of Rest as opposed to the grace of Action. These points have often been dwelt upon in my Lectures; but I was never able completely to illustrate them by any single piece of Art, until I saw and drew this one. For the fact is that the Greeks did not arrive themselves at these three principles at the same time. They did not reach their perfect Naturalism till they had lost their love of Symmetry and order; and it is only in this inherited school of Greek work at Pisa in the xiith century that the entire unity of their qualities may be seen in balance. It will be felt at once how the quiet Humanity of this E. Head differs from everything Norman or German of the same period, how the exquisite order of its hair, of the folds of the beard, and of the leafage by which it is encompassed, separates itself from the confused intricacy of Arabic or other barbarous ornamentation, and, lasly, how the more or less undulating languid grace of its undulating curves expresses a temper, capable of Action in deed, but triumphing in Repose, while the elasticity and spring of Gothic foliage as distinctly indicates a temper incapable of Rest, unless fatigued. The introduction of the red and black Mosaic on the flat ground and the black beads in the eyes complete the piece of work as a general symbol of all that the Greeks meant to praise by their term ποικιλία.