Browse: 1470 objects

- Reference URL

Actions

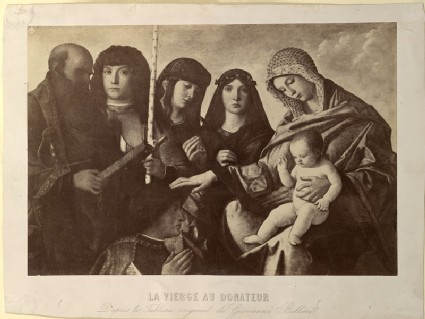

Photograph of Giovanni Bellini's "Virgin and Child with four Saints and a Donor" Goupil et Compagnie

-

Curator’s description:

Description

The religious figures are all shown three-quarter length. The Virgin sits on the right, holding the naked infant Christ on her left knee with her left hand, and reaches the other out into the centre of the picture to touch the head of the donor who kneels before her. The four saints stand to the Virgin's left, and are, from left to right: St Paul, holding his open book before him and with the hilt of his large sword in the crook of his left arm; St George, wearing chain mail and a breastplate and holding the pale shaft of his spear; and two unidentified young female saints, on eof whom Ruskin presumably identified as Saint Catherine.

According to Cook and Wedderburn (XXI.13 n. 2), 'The photograph ... is of a picture, formerly in the Pourtalès Collection and now lost sight of. ... It is impossible to say whether the photograph is the example which Ruskin intended by his title, or whether he had subsequently substituted it for one of some other picture by Bellini.' The painting in question, usually attributed to Giovanni Bellini working with assistance from his workshop (Lattanzio da Rimini and Marco Bello have been suggested as the workshop assistants) and painted c.1500, is now in the Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Neither of the two works which Cook and Wedderburn suggested were originally reproduced in this frame (Bellini's "Virgin, St Paul and St George" in the Accademia, or his "Virgin with St John and St Catherine" in the Redentore, often given to Bissolo) are convincing.

The photograph was first listed in the collection in 1870, as no. 5 in the Standard Series, in the "Catalogue of Examples". For Ruskin, this picture (whichever it was) was 'the best that has yet been done by man in art ... counting by the sum of qualities in perfect balance'. He considered it errorless in workmanship (and therefore in all other matters), faultless, truly devotional, sublime and precise.

-

Details

- Artist/maker

-

Goupil et Compagnie (photographer)after Giovanni Bellini (c. 1431/6 - 1516)

- Object type

- photograph

- Material and technique

- albumen print

- Dimensions

- 162 x 236 mm (object); 203 x 271 mm (original mount)

- Inscription

- Within the image:

photographed, on a label applied to the painting in its top left corner: 44

bottom centre, blind-stamped: GOUPIL & CIE.

On the mount, bottom centre, printed: LA VIERGE AU DONATEUR | D'apres le Tableau original de Giovanni Bellini

On the back of the mount:

top right, in graphite (recent): ST 5 | = Pierpont Morgan | Santa Conversazione | (Dussler,pl. 138)

just above centre, towards left, the Ruskin School's stamp

- Provenance

-

Presented by John Ruskin to the Ruskin Drawing School (University of Oxford), 1875; transferred from the Ruskin Drawing School to the Ashmolean Museum, c.1949.

- No. of items

- 1

- Accession no.

- WA.RS.STD.005

-

Subject terms allocated by curators:

Subjects

-

References in which this object is cited include:

References

Ruskin, John, Catalogue of Examples Arranged for Elementary Study in the University Galleries (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1870), cat. Standard no. 5

Ruskin, John, Catalogue of the Reference Series Including Temporarily the First Section of the Standard Series (London: Smith, Elder, [1872]), cat. Standard no. 5

Ruskin, John, ‘The Ruskin Art Collection at Oxford: Catalogues, Notes and Instructions’, Edward T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn, eds, The Works of John Ruskin: Library Edition, 39 (London: George Allen, 1903-1912), 21, cat. Standard no. 5

Ruskin, John, ‘The Eagle's Nest: Ten Lectures on the Relation of Natural Science to Art, Given Before the University of Oxfored, in Lent Term, 1872’, Edward T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn, eds, The Works of John Ruskin: Library Edition, 39 (London: George Allen, 1903-1912), 22

Location

-

- Western Art Print Room

Position in Ruskin’s Collection

Ruskin's Catalogues

-

Ruskin's Catalogue of Examples (1870)

5. The Virgin with St. George and St. Catherine. (John Bellini.)This is the most accurate type I can find of the best that has yet been done by man in art;—the best, that is to say, counting by the sum of qualities in perfect balance; and ranking errorless workmanship as the first of virtues, generally implying, in an educated person, all others. A partially educated man may do his mechanical work well, yet have many weaknesses: his precision may even be a sign of great folly or cruelty; but a man of richly accomplished mind, who does his mechanical work strictly, is likely to be in all other matters right.

This picture has no fault, as far as I can judge. It is deeply, rationally, unaffectedly devotional, with the temper of religion which is eternal in high humanity. It has all the great and grave qualities of art, and all the delicate and childish ones. Few pictures are more sublime, and none more precise. It will serve us in innumerable ways for future reference; and I like to place it beside Dürer’s solemn engraving on account of the relations of these two men at Venice.

Dürer’s words respecting this matter are usually quoted somewhat inaccurately. Here is the quaint old German in, I believe, its authentic form, as it was written to Wilibald Pirkheimer, in Nürnberg, from Venice, 9’ of the night, Saturday after Candlemas, 1506 (7th February):—

Ich hab vill guter freund under den Walhen (Wälschen;—Italians), dy mich warnen, das Ich mit Iren Molern nit es und trinck. Auch sind mir Ir vill feind, und machen mein ding in kirchen ab, and wo sy es mügen bekumen, noch schelten sy es und sagen es sey nit antigisch art, dozu sey es nit gut; aber Sambellinus der hatt mich vor vill gentilomen fast ser gelobt, er wolt gern etwas von mir haben, and ist selber zu mir kumen, und hat mich gepetten, Ich soll Im etwas machen, er wols woll tzalen. Und sagen mir dy leut alle, wy es so ein frumer man sey, das Ich Im gleich günstig pin. Er ist ser alt and ist noch der pest im gemell, und das ding das mir vor eilff jorn so woll hat gefallen das gefelt mir jtz nit mer Von Murr, Journal zur Kunstgeshichte x. p. 8. Nürnberg, 1781. Found and translated for me by Mr. R. N. Wornum. .

I have many good friends among the Italians, who warn me not to eat and drink with their painters. Many also of them are my enemies; they copy my things for the churches, picking them up whenever they can. Yet they abuse my style, saying that it is not antique art, and that therefore it is not good. But Giambellini has praised me much before many gentlemen; he wishes to have something of mine; he came to me and begged me to do something for him, and is quite willing to pay for it. And every one gives him such a good character that I feel an affection for him. He is very old, and is yet the best in painting; and the thing which pleased me so well eleven years ago has now no attractions for me (speaking of his own work, I presume).

-

Ruskin's Standard & Reference series (1872)

5. The Virgin with St. George and St. Catherine. (John Bellini.)This is the most accurate type I can find of the best that has yet been done by man in art;—the best, that is to say, counting by the sum of qualities in perfect balance; and ranking errorless workmanship as the first of virtues, generally implying, in an educated person, all others. A partially educated man may do his mechanical work well, yet have many weaknesses: his precision may even be a sign of great folly or cruelty; but a man of richly accomplished mind, who does his mechanical work strictly, is likely to be in all other matters right.

This picture has no fault, as far as I can judge. It is deeply, rationally, unaffectedly devotional, with the temper of religion which is eternal in high humanity. It has all the great and grave qualities of art, and all the delicate and childish ones. Few pictures are more sublime, and none more precise. It will serve us in innumerable ways for future reference; and I like to place it beside Dürer’s solemn engraving , on account of the relations of these two men at Venice.

Dürer’s words respecting this matter are usually quoted somewhat inaccurately. Here is the quaint old German in, I believe, its authentic form, as it was written to Wilibald Pirkheimer, in Nürnberg, from Venice, 9’ of the night, Saturday after Candlemas, 1506 (7th February):—

Ich hab vill guter freund under den Walhen (Wälschen;—Italians), dy mich warnen, das Ich mit Iren Molern nit es und trinck. Auch sind mir Ir vill feind, und machen mein ding in kirchen ab, und wo sy es mügen bekumen, noch schelten sy es und sagen es sey nit antigisch art, dozu sey es nit gut; aber Sambellinus der hatt mich vor vill gentilomen fast ser gelobt, er wolt gern etwas von mir haben, und ist selber zu mir kumen, und hat mich gepetten, Ich soll Im etwas machen, er wols woll tzalen. Und sagen mir dy leut alle, wy es so ein frumer man sey, das Ich Im gleich günstig pin. Er ist ser alt und ist noch der pest im gemell, und das ding das mir vor eilff jorn so woll hat gefallen das gefelt mir jtznit mer. Von Murr, Journal zur Kunstgeschichte, x. p. 8. Nürnberg, 1781. Found and translated for me by Mr. R N. Wornum.

I have many good friends among the Italians, who warn me not to eat and drink with their painters. Many also of them are my enemies; they copy my things for the churches, picking them up whenever they can. Yet they abuse my style, saying that it is not antique art, and that therefore it is not good. But Giambellini has praised me much before many gentlemen; he wishes to have something of mine; he came to me and begged me to do something for him, and is quite willing to pay for it. And every one gives him such a good character that I feel an affection for him. He is very old, and is yet the best in painting; and the thing which pleased me so well eleven years ago has now no attractions for me (speaking of his own work, I presume).