Ruskin's Catalogue of Examples (1870)

Ruskin's first catalogue with notes containing his plans for the Standard, Reference and Educational series.

Ruskin's Catalogues: 1 object

Show search help© Sackler Library, courtesy of the Oxford Digital Library and University of Oxford Department of Oriental Studies "Digitization of Champollion and Rosellini" project

- Reference URL

Actions

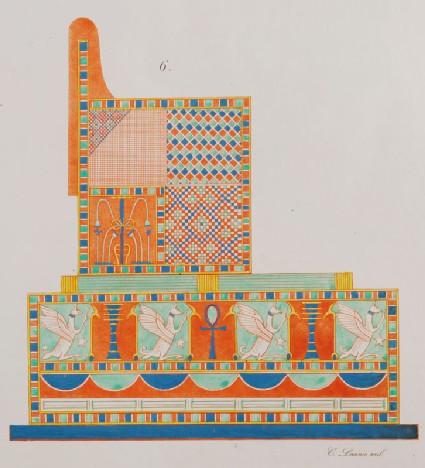

Engraving of an Egyptian Block Throne, from an unidentified Original Anonymous Italian

-

Ruskin text

14. Egyptian chair.Rosellini, Tavole, tom. ii. pl. 90, No. 6.Try, at all events, to do some portion of this example. It is coloured by hand, and will give you simple but severe discipline in laying flat colour in small portions.

And now, note that there are two distinct modes of excellence in laying water-colour. Its own speciality is to be mixed with much water, and laid almost as a drop or splash on the paper, so that it dries evenly and with a sharp edge. When so laid, the colour takes a kind of crystalline bloom and purity as it dries, and is as good in quality as a tint of the kind can be. The two little drawings of Turner’s, 45 and 46 , and nearly all his early work, are laid with transparent colour in this way. The difference between good painting and bad painting in this manner, is, that a real painter is as careful about the outline of the tint, laid liquid, as if it were laid thick or nearly dry, while a bad painter lets the splash outline itself as it will.

The exercises from Egyptian furniture and dress are intended to cure you at once of any carelessness of this kind. They are to be laid with perfectly wet colour, so that the whole space you have to fill, large or small, is to be filled before any of the colour dries; and yet you are never to go over the outlines. The leaf exercises (41 B, C, and D) are easier practice of the same kind. You had better do them first, though they are put, for other reasons, with the more advanced series. The white nautilus shell (47 C) is entirely painted with small touches of very wet colour of this kind, in order to get as much transparency into the structure of the tint as is possible. So also the shadows of the piece of sculpture (25). The exquisitely skilful drawing of Prout’s interior (29, right hand), owes much of its effect of light to the perfect flatness of the wet tints; and the character of the crumbling stone in the gable of Amiens (24) is entirely got by using the colour very wet, and leaving its dried edge for an outline when it is needed.

The simplest mode of gradating tints laid in this manner, when they extend over large spaces, is by adding water; but a good painter can gradate even a very wet tint by lightness of hand, laying less or more of it, so that in some places it cannot be seen when it ends. The beautiful light on the rapid of the Tees (S. 2) is entirely produced by subtlety of gradation in wet colour of this kind.

But, secondly, by painting with opaque colour, or with any kind of colour ground so thick as to be unctuous, not only the most subtle lines and forms may be expressed, but a gradation obtained by the breaking or crumbling of the colour as the brush rises from the surface—a quality all good painters delight in.

For all the exercises, therefore, which consist of lines to be drawn with the brush, prepare a mixture of Indian red with violet carmine, of a full, dark, and rich consistence. Fill your brush with it; then press out on the palette as much as will leave the brush not heavily loaded, and with a nice point, and then draw the line slowly; at once, if possible; but where it fails, re-touch it, the object being to get it quite even throughout, whether thin or thick. It may be thickened when you miss a curve, to get it right, and it may taper to nothing when it vanishes in ribs of leaves, &c.; but it must never be made thin towards the light, and thick towards the dark, side. It expresses only the terminations of form, not the lighting of it.

I have left my lines, in nearly every case, with their mistakes and re-touchings unconcealed, and have not tried always to do them as well as I could; so that I think you will generally be able to obtain an approximate result.

-

Curator’s description:

Description

The print shows a block throne on a dais, both decorated with geometric patterns, and the dais with winged rekhyt (lapwings) and the hieroglyphs for 'life, power, stability'.

It is part of a series representing various Egyptian furnishings and domestic goods, and is taken from the second volume of plates from Ippolito Rosellini's "Monumenti dell' Egitto e della Nubia", published in 1834. Unfortunately, Rosellini does not discuss this particular throne, or identify the site of the original representation from which it was copied. It was first catalogued by Ruskin in the "Catalogue of Examples" of 1870, as no. 14 in the Educational Series, where he entitled it "Egyptian chair". However, it did not reappear in any of his subsequent catalogues, and so was not part of the collection transferred to the University in the Deed of Gift of 31 May 1875. As it can no longer be found, it is represented here by a plate from the volume in the Sackler Library of the University of Oxford.

The draughtsman of the original cannot be identified with certainty: listed on the bottom left of the sheet from which this image is taken as 'Ros.', it may have been either Ippolito Rosellini or Gaetano Rosellini.

In a note in "The Ethics of the Dust", explaining how the individual aspects of the Egyptian deities were still largely unknown, Ruskin was somewhat sceptical of Rosellini's qualities: 'for the full titles and utterances of the gods, Rosellini is as yet the only - and I believe, still a very questionable - authority' (Ethics of the Dust, note III = XVIII.363). In his entry below nos 176-180 in the Reference Series, Ruskin again questioned Rosellini's accuracy, noting that the colours were sometimes conjectural, 'slight traces of the original pigments, and those changed by time, being interpreted often too arbitrarily' (Standard and Reference Series catalogue, p. 22).

-

Details

- Artist/maker

-

Anonymous Italian (Anonymous, Italian)Carlo Lasinio (1759 - 1838) (engraver)

- Object type

- Material and technique

- watercolour and bodycolour over etching on wove paper

- Dimensions

- [210 x 197 mm (approx., stone)]

- Inscription

- Recto, engraved:

above the chair, centre: 6.

bottom right: C. Lasinio scul.

- Provenance

-

Recorded in the Ruskin Drawing School (University of Oxford), in 1870; not recorded in the collection subsequently.

- No. of items

- 1

- Accession no.

- EXAMPLES.ED.014.a

-

Subject terms allocated by curators:

Subjects

-

References in which this object is cited include:

References

Ruskin, John, Catalogue of Examples Arranged for Elementary Study in the University Galleries (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1870), cat. Educational no. 14

Rosellini, Ippolito, I monumenti dell' Egitto e della Nubia: Disegnati dalla spedizione scientifico-letteraria toscana in Egitto: distributi in ordine di materie, 12 (Pisa: Presso N. Capurro, 1832-1844), pt II, Tavole, pl. XC, fig. 6

Ruskin, John, ‘The Ruskin Art Collection at Oxford: Catalogues, Notes and Instructions’, Edward T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn, eds, The Works of John Ruskin: Library Edition, 39 (London: George Allen, 1903-1912), 21

Location

-

- not found

Ruskin's Catalogues

-

Ruskin's Catalogue of Examples (1870)

14. Egyptian chair.Rosellini, Tavole, tom. ii. pl. 90, No. 6.Try, at all events, to do some portion of this example. It is coloured by hand, and will give you simple but severe discipline in laying flat colour in small portions.

And now, note that there are two distinct modes of excellence in laying water-colour. Its own speciality is to be mixed with much water, and laid almost as a drop or splash on the paper, so that it dries evenly and with a sharp edge. When so laid, the colour takes a kind of crystalline bloom and purity as it dries, and is as good in quality as a tint of the kind can be. The two little drawings of Turner’s, 45 and 46 , and nearly all his early work, are laid with transparent colour in this way. The difference between good painting and bad painting in this manner, is, that a real painter is as careful about the outline of the tint, laid liquid, as if it were laid thick or nearly dry, while a bad painter lets the splash outline itself as it will.

The exercises from Egyptian furniture and dress are intended to cure you at once of any carelessness of this kind. They are to be laid with perfectly wet colour, so that the whole space you have to fill, large or small, is to be filled before any of the colour dries; and yet you are never to go over the outlines. The leaf exercises (41 B, C, and D) are easier practice of the same kind. You had better do them first, though they are put, for other reasons, with the more advanced series. The white nautilus shell (47 C) is entirely painted with small touches of very wet colour of this kind, in order to get as much transparency into the structure of the tint as is possible. So also the shadows of the piece of sculpture (25). The exquisitely skilful drawing of Prout’s interior (29, right hand), owes much of its effect of light to the perfect flatness of the wet tints; and the character of the crumbling stone in the gable of Amiens (24) is entirely got by using the colour very wet, and leaving its dried edge for an outline when it is needed.

The simplest mode of gradating tints laid in this manner, when they extend over large spaces, is by adding water; but a good painter can gradate even a very wet tint by lightness of hand, laying less or more of it, so that in some places it cannot be seen when it ends. The beautiful light on the rapid of the Tees (S. 2) is entirely produced by subtlety of gradation in wet colour of this kind.

But, secondly, by painting with opaque colour, or with any kind of colour ground so thick as to be unctuous, not only the most subtle lines and forms may be expressed, but a gradation obtained by the breaking or crumbling of the colour as the brush rises from the surface—a quality all good painters delight in.

For all the exercises, therefore, which consist of lines to be drawn with the brush, prepare a mixture of Indian red with violet carmine, of a full, dark, and rich consistence. Fill your brush with it; then press out on the palette as much as will leave the brush not heavily loaded, and with a nice point, and then draw the line slowly; at once, if possible; but where it fails, re-touch it, the object being to get it quite even throughout, whether thin or thick. It may be thickened when you miss a curve, to get it right, and it may taper to nothing when it vanishes in ribs of leaves, &c.; but it must never be made thin towards the light, and thick towards the dark, side. It expresses only the terminations of form, not the lighting of it.

I have left my lines, in nearly every case, with their mistakes and re-touchings unconcealed, and have not tried always to do them as well as I could; so that I think you will generally be able to obtain an approximate result.